Seagrass struggles for attention, conservation

By Vin Se

“I told myself, we have a lot of this plant in the Philippines, but nobody ever bothered to study it,” University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute retired professor, coastal ecologist Miguel Fortes said involvement in seagrass research began in the early 1980s, on an island in Germany where seagrasses used to thrive. One day, a colleague ran toward him excitedly, with seagrass in hand.

Three decades later, seagrass remains the least studied among coastal habitats despite providing plethora of highly valuable ecosystem services and nature-based solutions to tackle the impacts of climate change.

In the Philippines, there are many unknowns about status of seagrass unlike coral reefs and mangroves that more researchers focus on. In his studies, Fortes said seagrass ecosystem has been focus of scientific inquiry only in the last 30 years, and as an object of conservation in the last 15 years.

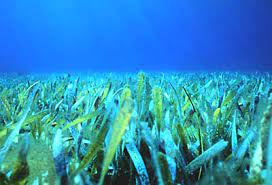

Seagrasses are marine flowering plants that are found in shallow water. They improve water quality, support rich marine biodiversity, and provide food and livelihood to people.

For a country like Philippines vulnerable to climate-related impacts, seagrass meadows provide opportunities to mitigate climate change.

They are highly efficient carbon sinks, sequestering carbon from atmosphere up to 35 times faster than tropical rainforests. This ecosystem can also help protect coastal areas by reducing wave energy.

Philippines has one of the highest seagrass species diversity in the world, with 18 known species across archipelago.

World Bank studies showed 27,000 square kilometers of seagrass meadows in the country in 2015. National Mapping and Resource Information Authority initial study in 2016 showed much lower figure of 4,700 square kilometers.

“Our efforts to validate and monitor on the ground are ongoing but definitely there’s a decline,” Biodiversity Management Bureau senior ecosystems management specialist Criselda Castor stressed.

BMB is an agency under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

Coastal developments, nutrient run-off, unregulated fishing and boating activities, and climate change are among main threats to seagrass meadows.

These highlight need for urgent conservation attention but seagrass remains an overlooked ecosystem.

Fortes, whose works serve as foundation for seagrass research in the Philippines, said lack of interest in seagrass is rooted in the perception that the ocean should be viewed as deep-water mass, with deep-sea fisheries and navigation as main uses.

“Viewing shallow portion with coral reefs and fringing mangroves as important for tourism and fisheries was recent development…seagrass has never been comparatively that visible, since less attractive ecosystem is sandwiched between other two ‘more important’ habitats, hence, with this sad scenario, we cannot expect capacity to be built, much less management policies to be developed specific for seagrass, ” Fortes said.

Mapping seagrass meadows is an important step in any initiative to protect these habitats as it gives researchers idea how big and how healthy meadows are.

The Berkeley, California-based nonprofit Seacology is spearheading Philippine Seagrass Project, aims to promote awareness and conservation of seagrass species in local waters.

It also mapped seagrass meadows in Puerto Galera ,Oriental Mindoro . The data gathered will be incorporated in mobile application that can be downloaded for free.

“You have to know where they are so you can protect them…for grassroot communities, it’s vague…they ask ‘where are seagrasses…are green ones we’re seeing seagrasses…so there’s lack of knowledge and people do not realize how important they are,” Seacology Philippines field representative Ferdie Marcelo said in a 2018 study said possible solution to lack of appreciation for seagrass is conducting an economic valuation to list how it benefits communities.

“The economic benefits of seagrasses have to be emphasized to the grassroots, the actual users…they can’t connect seagrasses to their income…there has to be a connection so they will see the need to protect seagrass,” Marcelo said.

BMB’s Castor said valuation of seagrasses is “in the pipeline.” In an emailed response, DENR’s Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau (ERDB) said currently implementing valuation of goods and services of coastal ecosystems in Batangas.

The Coastal and Marine Ecosystems Management Program (CMEMP) was established through an administrative order in 2016. The program is meant to comprehensively manage and effectively reduce drivers of degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems such as seagrass meadows.

Under the CMEMP, the department is conducting habitat assessment and monitoring to establish trends on the condition of seagrasses, and capacity building on how to assess seagrass beds. The program also has a maintenance and protection component.

For its part, ERDB has ongoing efforts to assess blue carbon sequestration potential of seagrass, the productivity of seagrass, and the carrying capacity of popular coastal tourist destinations.

Castor said government is “trying” to craft management policies specific to seagrass. In the meantime, BMB is lobbying for inclusion of neglected but important ecosystem in the design of Marine Protected Areas.

It is also pushing to incorporate seagrass in legislative measures such as the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act.

Future of seagrass research and conservation is “much brighter now,” Fortes thanks emerging interest and expertise in the last decade. But more needs to be done by policymakers, scientists, and communities to conserve seagrass meadows.

One way to encourage more students and scientists to study seagrass is for educators to stress that coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass are one natural continuum that needs collective understanding, protection, and support, Fortes said.

“They need to emphasize application of seagrass knowledge in solving common issues pollution, food shortage, climate change, coastal degradation, and ineffective conservation laws,” he said.

The scientist said policymakers should think outside box and “look at the forest, not just the trees.”

Fortes said there are very few efforts to link seagrass science, policy and practice on the ground due to inadequate interaction among primary stakeholders.

“Key is constant dialogue with stakeholders and for the ‘educated’ to go down from their pedestal and offer service direct to the communities that need it most,” Fortes concluded.